There are several scientific studies on the cloak (tilma) of the Mexican Saint Juan Diego, on which the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe was miraculously imprinted on December 12th,1531, and which remains intact to this day.

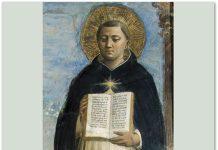

Original image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, photographed in October 2017 – Basilica of Santa Maria de Guadalupe, Mexico. Photos: Lúcio Alves

Newsdesk (05/08/2025 09:42, Gaudium Press) The website La Nuova Bussola interviewed David Caron Olivares, author of the book Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. La Imagen ante el reto de la Historia y de la Ciencia (Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Image Facing the Challenge of History and Science), after a conference on the subject in Italy, held on July 22nd at the Milanese sanctuary of Santa Maria alla Fontana.

Below is a translation of the interview.

Over the centuries, various scientific studies have been conducted on the tilma bearing the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe: what do these studies tell us?

We summarize some of the facts related to the image imprinted on Saint Juan Diego’s tilma that are inexplicable to science:

The fabric of the tilma is still intact and has not deteriorated, despite being made of a vegetable fibre that normally disintegrates into small fragments in less than twenty years. This fabric has not suffered the slightest deterioration, neither from contact with the crowd, nor from the smoke of countless candles, nor from dust, despite having been exposed without any protection for 116 years before the first protective glass was placed over it in 1647.

The extraordinary delicacy of the image, impossible to achieve even by an experienced painter on this rough surface and without any prior preparation of that surface.

The colours retain an extraordinary luminosity, when they should have faded, changed tone and cracked, as they are not protected by any varnish.

In 1785, a highly concentrated and corrosive acid, similar to nitric acid, was poured over the image without destroying the fabric.

The corneas and pupils of the Virgin’s eyes reflect the people present in the bishop’s chamber during the moment of revelation of the image on the cloak. These reflections were discovered only in the 20th century through studies by scientists specializing in ophthalmology.

The stars on the mantle correspond to the Northern and Southern constellations visible from Mexico on December 12th, 1531, the day of the last apparition of Our Lady to Juan Diego.

In 1921, a bomb exploded in front of the image, leaving it intact, while a crucifix that was in the same location was visibly damaged.

Among the first to delve into the mystery of the image imprinted on Saint Juan Diego’s cloak were some painters, mainly in the 17th and 18th centuries. What did the research and pictorial experiments carried out on the tilma reveal?

The image was studied by several groups of painters and doctors, particularly in 1666 and 1751.

In 1666, seven great painters from New Spain examined the image directly and published the results of their expertise. They declared that it was impossible for an artist to paint such a work on such coarse fabric and achieve such beauty in the face. A supernatural work, they said. At the same time, three doctors came to the same conclusion: ‘Humanly speaking, it is not possible to explain the phenomenon observed.’ The three doctors unanimously declared that – due to the high humidity present in the chapel, caused by the air coming from the lake system of Mexico, and the strong presence of salts in the air coming from the salt river of Tlalnepantla (no longer existing today) – the image, exposed to the open air, should show a large number of obvious signs of corrosion. The preservation of the fabric and the image printed on it are inexplicable, considering the humidity that surrounds them and the salty atmosphere that affects even metals; the colours are impregnated in the fabric in such a way that they pass through it and make it visible on the back of the image, which shows that the fabric had not been prepared for painting, making it inexplicable that the image is still there.

With the approval of the Council of the Shrine of Guadalupe on April 30th, 1751, Miguel Cabrera and six other painters undertook a thorough examination of the image, removing it from its frame and taking off the glass that protected it. What were their conclusions?

a) the durability of the fabric is inexplicable, considering its 220 years of age at the time;

b) the tilma is made of a fabric of vegetable origin;

c) the fabric was not previously prepared for painting and the image is visible from the back;

d) the design and features of Our Lady are impeccably proportioned and drawn.

This great Mexican painter, Miguel Mateo Maldonado y Cabrera, founded Mexico’s first painting academy in 1753 and wrote, in 1756, an important treatise entitled Maravilla Americana y Conjunto de Raras Maravillas Observadas Según las Reglas del Arte y la Pintura (American Marvel and Collection of Rare Wonders Observed According to the Rules of Art and Painting), in which he evokes the perfection of the image from an artistic point of view. He showed how the artist used the defects of the canvas to represent the face: ‘The mouth is a marvel, it has very thin lips and the lower lip falls mysteriously into a defect or knot in the canvas, to give the grace of a slight smile’.

Some are sceptical about the miraculous origin of the tilma, highlighting the presence of some secondary human interventions, such as the silver of the moon, the gold of the sun’s rays and the stars, and the white of the clouds. When did these interventions occur? And why do they not diminish the miraculous event that took place on December 12th, 1531?

Some of these interventions are contemporary to the miraculous apparition of 1531, others are later. Although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact dates of each one, it is known that, over the centuries, touch-ups and repainting were done at different times. However, these human interventions do not diminish the miracle of the apparition of the image for several fundamental reasons. The original image is inexplicable; the most rigorous scientific studies of the tilma over the centuries have found characteristics that defy any human or technical explanation known at the time, such as: the durability of the fabric, the absence of brushstrokes, the reflections in the eyes that correspond to those that would be produced in a human eye, etc.

One of the most famous scientific studies was conducted in 1936 by Richard Kuhn, future Nobel Prize winner in Chemistry. What did Kuhn discover with his analyses of the tilma?

Human interventions are limited to a few details and are superficial, without affecting the essence or mystery of the main image. In other words, what is considered miraculous is the very existence of the image and its inexplicable properties on the agave fabric (NT. the textile fibre extracted from agave is sisal), not the minor retouches that may have been added in later periods for reasons of devotion or embellishment. In summary, sceptics may highlight human interventions, but these are secondary elements that neither alter nor refute the extraordinary and scientifically inexplicable properties of the original image on the tilma, which remains the centre of the miracle of Guadalupe.

Kuhn reached some very surprising conclusions, indicating that neither of the two fibres examined, one red and the other yellow, contained any type of pigment known in nature, whether in the plant, animal or mineral kingdom. These were therefore unknown dyes. Synthetic dyes were excluded from the debate, as they were not used until the second half of the 19th century. Therefore, they cannot be present in the tilma, which dates from the 16th century.

The image of the Virgin of Guadalupe is rich in highly symbolic elements, from her Mestizo face to her dark belt, to her blue cloak covered with stars. What do these symbols tell us? And how did they contribute to evangelization in the Mexican and American context in general?

This image is a code, a pictographic script that must be deciphered. The Virgin in the image is surrounded by rays of sunlight; beneath her feet is a crescent moon. The Virgin is pregnant, as evidenced by the black belt with a double knot that Aztec women wore around their waists during pregnancy and the four-petalled flower on her belly. In the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the Bishop recognised the woman from chapter 12 of Revelation: ‘A great sign appeared in the sky: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head. She was with child (…)’. For the Aztecs, this four-petalled flower called Nahui Ollin summed up all the knowledge of the world, the manifestation of God. The Nahui Ollin flower is placed on the belly of the miraculous image, announcing to the Aztecs that the being She carries within Her is the true God. We also see a series of flowers, which have their roots in the mantle, representing the sky. These flowers are, therefore, a symbol of Divine Truth. The catechized indigenous people understood that the long-awaited promise of the beginning of a new era, under a new sun, would be fulfilled with the birth of the true God, Jesus, whom the Virgin of Guadalupe carries in Her womb.

From all over, even from far away, the Indians flocked to Tepeyac. And baptisms multiplied. In eight years, nine million Indians and Spaniards requested this sacrament. It was one of the most impressive mass conversions in the history of the Church.

Our Lady performs the miracle of unity: since the conquest, unity between Indians and Spaniards had been seriously threatened. The conquerors wanted to enslave the indigenous people and exploit them commercially, which was directly opposed by the first evangelizers, whose lives were also in danger. This is one of the most powerful miracles: the total unity that She brings about in an apocalyptic moment. She unites these two civilizations, taking on the appearance of a Mestizo (mixed-race) woman during the apparition and announcing this message: ‘I am your Mother, I am the Mother of all humanity’.

As for the stars on the mantle of the Virgin of Guadalupe, it has been scientifically proven that they represent the stars of the constellations visible from the valley of Mexico City on December 12th. We recall that December 12th, in the Julian calendar, is the day of the winter solstice, which corresponded to the most important festival of the year for the Aztecs, the Panquetzaliztli, or indigenous ‘Easter’. The rising sun has won the battle against darkness, and the days begin to gain more vigour. A new cycle begins.

It should also be noted that the number of stars on the Virgin’s mantle (46), distributed in 23 stars on the left and 23 on the right, corresponds to the number of chromosomes in the cells of the human body (23 pairs). This observation suggests once again that every detail of the mantle has its reason for being. We can see in this a new symbol with which the Virgin wants to say that her intervention concerns all human beings and calls on all humanity to participate in the civilization of love.

Article written by Ermes Dovico, on August 1st, on the website lanuovabq.it. Translation by Gaudium Press.

Compiled by Roberta MacEwan