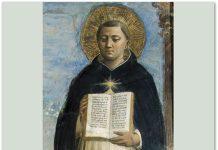

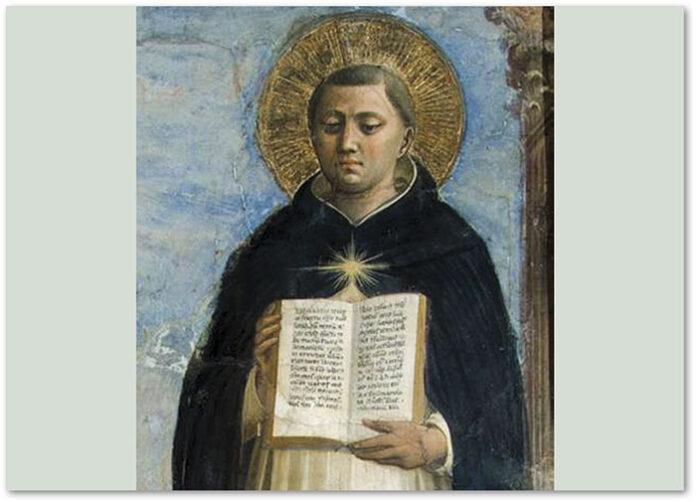

Exploring St. Thomas Aquinas’ extraordinary intellect, prolific writings, and the divine silence that crowned his life’s work.

Newsroom (28/01/2026 Gaudium Press )Few figures in the history of human thought stand as tall as St. Thomas Aquinas, whose feast the Catholic Church celebrates on January 28. Across two short decades, the Dominican friar produced an estimated 10 million words spanning roughly 60 treatises—an intellectual achievement unmatched in scope and endurance. Working at times with as many as four secretaries simultaneously, Aquinas dictated on distinct subjects with seamless precision.

To understand the magnitude of such productivity, imagine a prolific writer completing a hundred books in a lifetime, each 350 words long—that effort would total barely 35,000 words, a modest footnote beside Aquinas’s towering oeuvre. Yet, to honor him merely for his output would miss the deeper miracle of his work: the clarity and sanctity of his thought.

Philosopher Peter Kreeft calls Aquinas the greatest of philosophers—admired for his relentless pursuit of truth, his common sense, his practicality, and his unmatched clarity. Equally, he embodied profundity, orthodoxy, a true medieval spirit, and a penetrating critique of modernity. To maintain such intellectual integrity over a lifetime required something beyond reason—it demanded sanctity. For Aquinas, philosophy was not a game of ideas but a prayerful approach to reality itself.

The Road to Silence

Then, on the feast of St. Nicholas in 1273, an unexpected quiet fell upon the Angelic Doctor. Returning from celebrating Mass, Aquinas stopped writing. He laid aside his unfinished masterwork, the Summa Theologiae, and would never dictate another word.

His assistant, Reginald of Piperno, concerned by this sudden pause, pleaded with him to continue. Aquinas’s reply was brief and startling: “I can write no more.” When pressed again, he repeated, “All that I have written seems to me nothing but straw.” Later he enlarged upon this statement, adding, “…compared to what I have seen and what has been revealed to me.”

That silence speaks more powerfully than his millions of words. In that moment, Aquinas glimpsed truths so profound that human language could no longer suffice. The scholar became a mystic, surrendered to the ineffable. His silence echoed the very mystery he had spent his life explaining: that ultimate knowledge belongs to God alone.

The Mystery Beyond Words

The philosopher Josef Pieper, in his penetrating book The Silence of St. Thomas, interpreted this withdrawal not as exhaustion but as reverence. Aquinas, he wrote, was silent not for lack of insight but because he had seen too much. “He is silent because he has been allowed a glimpse into the inexpressible depths of that mystery which is not reached by any human thought or speech,” Pieper observed.

The event reminds believers that faith never contradicts reason—but surpasses it. The Apostle Paul’s words capture the point: “Eye has not seen, nor ear heard, nor have entered the heart of man the things which God has prepared for those who love him.” Aquinas’s silence bears witness to that truth—that even our deepest wisdom is but a threshold to divine mystery.

Beyond “Thomism”

It is tempting to speak of “Thomism” as though it were a closed system of thought. Yet Aquinas himself would have resisted such classification. His work is not an ideology but a living participation in truth—a truth that continues to unfold. To name it “Thomism” risks confining what Aquinas himself sought to keep open.

His thought flows within a larger tradition—one that welcomes further reflection across generations. In that sense, St. Thomas’s legacy remains alive not only in his words but also in the ongoing dialogue between faith and reason that he helped to define.

Enduring Recognition

The centuries have not dimmed Aquinas’s light. Successive popes have praised his genius as the Church’s perennial guide. Pope Leo XIII’s Aeterni Patris (1879) declared him “the chief and master of all Scholastics,” noting that he seemed to “have inherited the intellect of all” who came before. Pius X, in Doctoris Angelici (1914), described his mind as “almost angelic,” perfecting the harmony of inherited wisdom to defend divine truth. Pius XI, in Studiorum Ducem (1923), praised his moral virtue as a unified expression of charity. And Pius XII, in Humani Generis (1950), affirmed that Aquinas’s method remains “singularly preeminent” for bringing truth to light in harmony with revelation.

The Final Word

Ultimately, Aquinas’s lasting contribution is not confined to the brilliance of his theology or the scope of his philosophy. It rests in the humility of his ending—that moment when words ceased because something greater had been shown. The world received from Thomas not only vast knowledge, but also a profound lesson in silence: that God transcends even our most luminous thoughts.

In his quiet, Aquinas gave his final teaching—that truth, like God himself, is inexhaustible.

- Raju Hasmukh with files from NCR