Lemaître’s caution reminds us that true dialogue demands humility: science evolves, faith endures, and neither should be bent to serve the other.

Newsroom (23/09/2025, Gaudium Press ) The Big Bang theory, was first proposed by a Catholic priest nearly a century ago. And when Pope Pius XII appeared to champion it as proof of divine creation, the priest behind the concept urged the pontiff to tread carefully, emphasizing the separation between science and faith.

Rev. Georges Lemaître, a Belgian diocesan priest, theoretical physicist, and mathematician, developed the foundational ideas of the Big Bang in the late 1920s. Born in 1894 in Charleroi, Belgium, Lemaître entered seminary in 1911 but interrupted his studies to serve in World War I as an artillery officer in the Belgian army starting in 1914. He was ordained a priest for the Archdiocese of Mechelen-Brussels in 1923, having already earned a doctorate in mathematics and physics from the University of Louvain in 1920. Though often mistaken for a Jesuit due to his scholarly pursuits—a common mix-up for priest-scientists of his era—Lemaître remained a diocesan priest and a lifelong member of the Priestly Fraternity of the Friends of Jesus, a group founded by Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier to foster spiritual life among clergy.

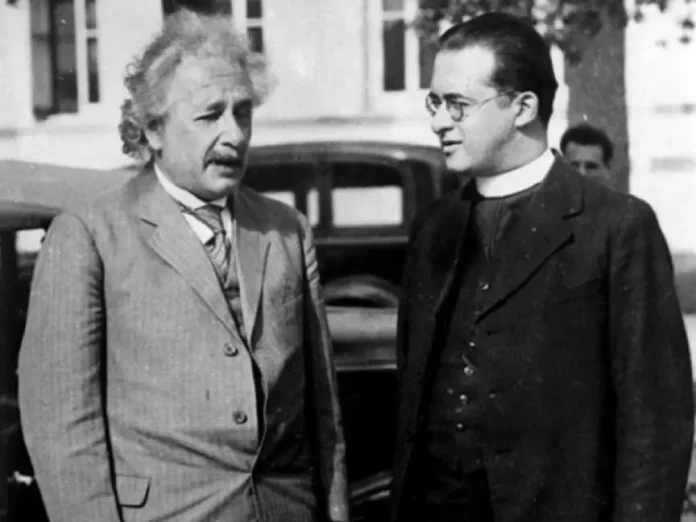

From 1927 until his retirement in 1964, Lemaître served as a professor of physics at the Catholic University of Louvain (now KU Leuven). That same year, he earned a second doctorate—a Ph.D. in physics—from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where his dissertation focused on the gravitational field in a fluid sphere according to relativity theory. Lemaître engaged deeply with leading figures in physics, including Albert Einstein, whose general theory of relativity formed the basis of his early research. A photograph from the era captures the two men together, symbolizing the intellectual exchange that shaped modern cosmology.

Between 1927 and 1931, Lemaître published his groundbreaking “hypothesis of the primeval atom,” positing that the universe originated from a single, supremely dense point—an “atomic nucleus” in his words—that exploded billions of years ago. This event, he argued, not only birthed all matter but also expanded space-time itself. The term “Big Bang” was later coined derisively by astronomer Fred Hoyle in 1949 to mock the idea, but it stuck. At the time, prevailing views, including Einstein’s, favored a static, eternal universe, making Lemaître’s dynamic model a radical departure. Over time, observational evidence—such as Edwin Hubble’s confirmation of galactic recession—led to its broad acceptance in the scientific community. Lemaître’s later work embraced emerging computational tools to model complex cosmological phenomena, foreshadowing today’s reliance on supercomputers for astrophysics.

Lemaître’s presence at the Vatican in 1951 added an unexpected chapter to his story. During an address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences on November 22, Pope Pius XII referenced recent cosmological advances, drawing parallels to the biblical creation narrative. “Indeed, it seems that the science of today, by going back in one leap millions of centuries, has succeeded in being a witness to that primordial Fiat Lux, when, out of nothing, there burst forth with matter a sea of light and radiation, while the particles of the chemical elements split and reunited in millions of galaxies,” the pope declared. He further noted that science had pinpointed the universe’s temporal beginning “at a period about five billion years ago,” interpreting this as “confirming with the concreteness of physical proofs the contingency of the universe and the well-founded deduction that about that time the cosmos issued from the hand of the Creator. Creation, therefore, in time, and therefore, a Creator; and consequently, God!”

Lemaître, seated in the audience as a member of the academy (appointed by Pope Pius XI in 1936), was taken aback. In the ensuing weeks, he and fellow scientists expressed concerns to the pope and his advisors, arguing that the remarks risked conflating a scientific hypothesis with theological doctrine. The Church’s support for science was a positive development, Lemaître acknowledged, but the pope had overstepped by presenting the Big Bang as definitive proof of Genesis—especially since the estimate of five billion years (now revised to approximately 13.8 billion based on modern data) was provisional.

To understand Lemaître’s stance, consider insights from a recent visit to America magazine by Br. Guy Consolmagno, S.J., the outgoing director of the Vatican Observatory, who stepped down in September 2025 after a decade in the role. Speaking last week, Consolmagno explained that Lemaître viewed the Big Bang as a testable hypothesis, subject to revision or refutation, not an unassailable truth akin to scriptural revelation. Several factors fueled Lemaître’s unease: the theory’s tentative nature, the danger of using science to “prove” faith (a form of concordism he rejected), and the need for theology and science to remain distinct yet complementary dialogues in pursuit of truth.

Lemaître himself had long advocated for this separation. In a 1936 lecture, he wrote: “He does this not because his faith could involve him in difficulties, but because it has directly nothing in common with his scientific activity. After all, a Christian does not act differently from any non-believer as far as walking, or running, or swimming is concerned.” For Lemaître, faith informed his worldview but did not dictate his scientific methodology—and vice versa.

This episode underscores a broader Catholic tradition of harmonizing faith and reason, from Galileo to today. As Pope Francis echoed in 2014, “The Big Bang… does not contradict the intervention of the divine creator, but… requires it.” Yet Lemaître’s caution reminds us that true dialogue demands humility: science evolves, faith endures, and neither should be bent to serve the other.

- Raju Hasmukh with files from americamagazine.org, vaticanobservatory.org, catholicscientists.org, luc.org, mit.edu