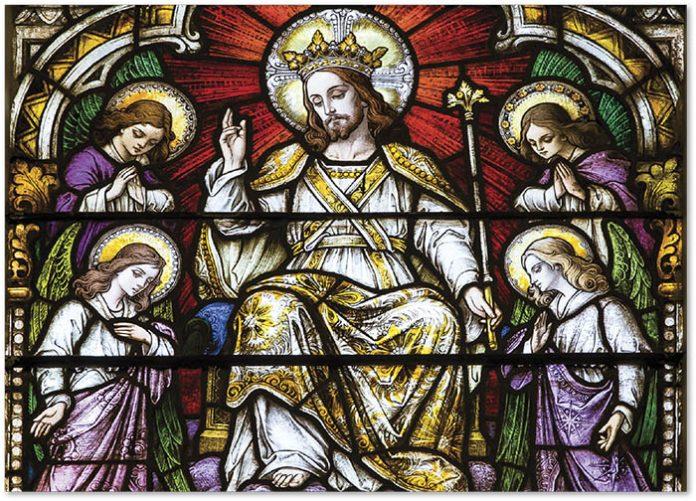

Established by Pius XI in 1925 amid rising secularism and dictatorship, the Solemnity of Christ the King reaffirms Jesus’ sovereign rule over individuals, nations, and history.

Newsroom (21/11/2025 Gaudium Press ) Rome, December 11, 1925 – In the encyclical Quas Primas, Pope Pius XI instituted the feast of Our Lord Jesus Christ the King, a solemnity that would come to close the liturgical year and stand as one of the most politically charged acts of the 20th-century papacy.

The world into which the new feast was born was still bleeding from the Great War. Europe lay in economic ruin, monarchies had collapsed, and the Treaty of Versailles had sown resentment that would soon bear poisonous fruit. From the ashes rose three men who promised order at any price: Benito Mussolini, already in power in Italy; Adolf Hitler, plotting in Munich beer halls; and Joseph Stalin, consolidating control in Moscow.

Against this backdrop of ideological extremism and aggressive secularism, many Catholics themselves began to treat faith as a purely private affair. Political movements—fascist, Nazi, and communist alike—openly sought to banish Christian influence from public life, education, and law. Even in traditionally Catholic nations, the prevailing attitude held that Christ might reign in hearts but had no claim on parliaments, courts, or classrooms.

Pius XI saw clearly what was at stake. Three years into his pontificate, he had already dedicated his reign to “the Peace of Christ in the Kingdom of Christ” (Pax Christi in Regno Christi). The Jubilee Year of 1925, marking the 1,600th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea—which had solemnly defined Christ’s full divinity and eternal kingship—provided the perfect occasion to drive the point home.

Throughout 1925, the Pope repeatedly emphasized the Nicene Creed’s declaration that Christ’s kingdom “will have no end.” The theme surfaced in the liturgies of the Annunciation, Epiphany, Transfiguration, and Ascension. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims streamed to Rome, their fervor confirming that the faithful hungered for a public reaffirmation of Christ’s universal lordship.

More than 340 cardinals, bishops, and religious superiors had formally petitioned the Holy See for a distinct feast honoring Christ’s kingship. On December 11, Pius XI granted their request with Quas Primas (“In the First”), an encyclical that remains one of the Church’s boldest assertions of the social kingship of Christ.

The Pope did not mince words. The “plague” afflicting modern society, he wrote, stemmed from the systematic rejection of Christ by nations and governments. “When once men recognize, both in private and in public life, that Christ is King,” he declared, “society will at last receive the great blessings of real liberty, well-ordered discipline, peace and harmony.”

He warned rulers directly: “Christ, who has been cast out of public life, despised, neglected and ignored, will most severely avenge these insults.” The state, he insisted, must conform its laws, justice, and education to divine and Christian principles, or face inevitable collapse.

Originally assigned to the last Sunday of October—positioned deliberately before All Saints’ Day to underscore both Christ’s present reign and his future judgment—the feast was celebrated with a plenary indulgence and an act of consecration to the Sacred Heart. Pius XI explicitly linked the new solemnity to Eucharistic devotion and reparation for the atheism sweeping Russia, Mexico, and elsewhere.

In 1969, Pope Paul VI elevated the celebration further. He renamed it “Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe” (Christus Universorum Rex), moved it to the final Sunday of the liturgical year—heightening its eschatological significance—and raised it to the rank of solemnity, the Church’s highest category of feast.

A century later, the world has changed, yet the diagnosis of Quas Primas feels eerily contemporary. Secular ideologies continue to demand absolute allegiance; laws are enacted with little or no reference to natural law or Gospel values; and public discourse often treats religious conviction as a private eccentricity rather than a claim on society itself.

Each November, as the Church’s liturgical year draws to a close, Catholics are given a yearly reminder—and a yearly challenge: Christ is not one king among many. He is the Alpha and the Omega, the one before whom every earthly power will ultimately bend the knee. In an age that still prefers self-made caesars to the crucified King, the Solemnity of Christ the King remains what Pius XI intended: a prophetic act of resistance and a summons to hope.

- Raju Hasmukh with files from OSV